Welcome!

Senior Research Scientist, Google DeepMind

PhD in Social and Engineering Systems and Statistics, MIT · Postdoctoral Fellow, Harvard · Postdoctoral Research Scientist, Meta FAIR

Interests: probabilistic modeling · multi-agent decision theory · network science · computational social choice · reinforcement learning from human feedback

I'm Manon, a researcher building mathematical and computational models for collective agency in a networked, AI-mediated world. My work brings together applied mathematics, AI, and political theory to design and analyze systems for collaborative decision-making—across human groups, democratic institutions, language models, and recommender systems.

During my PhD at MIT, I developed new probabilistic frameworks for multi-agent decision-making, with a particular focus on liquid democracy—a scheme where individuals delegate decisions dynamically using second-order knowledge (what I know about what you know). I combined formal theory with empirical methods, leading the first laboratory experiments on liquid democracy.

I was an adjunct professor at Notre Dame University, a lecturer at MIT, and a Democracy Doctoral Fellow at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance at the Harvard Kennedy School. I also led the research agenda on AI and democracy at the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard Law School and worked at Palantir, the Responsible AI Institute, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and Bell Labs.

Highlights

-

2026

🥁AI-Enhanced Deliberative Democracy and the Future of the Collective Will accepted by Philosophy & Technology

🥁Cultivating pluralism in algorithmic monoculture: The community alignment dataset (lead by Lily Zhang and Smitha Milli) accepted at ICLR

-

2025

🥁Representative Ranking for Deliberation in the Public Sphere accepted at ICML

🎓 Fun week at a16z as a Research Visitor to engage with the a16z Crypto Research Internship Program

🥁Democratic AI is Possible. The Democracy Levels Framework Shows How It Might Work accepted at ICML

🥁Arbiters of Ambivalence: Challenges of using LLMs in No-Consensus Tasks accepted at ACL

🎙 Joined the LSE-NYU Conference on Political Economy, the Cooperative AI Foundation to talk about AI & Deliberation and UrbanAI to discuss Collective Agency In An AI-Mediated World

🎙 Joined the Knight Symposium on AI & Democratic Freedoms to discuss our recent work on ranking algorithms that represent opinion pluralism

🎙 Shared thoughts on AI and society in the AI documentary on French TV De l'Homme à la Machine

🎓 Shared insights on AI-facilitated collective judgment at Oxford's Institute for Ethics in AI

🥁Tracking Truth with Liquid Democracy published in Management Science

-

2024

🎙 Interviewed Mistral AI CEO Arthur Mensch, LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman and Publicis President Maurice Lévy! An hour of stellar discussion about the future of AI and Europe

🥁SEAL: Systematic Error Analysis for Value ALignment accepted at AAAI-25 for an oral presentation

🎙 Interviewed on the Computing Up podcast: Democracy, A Comma in History?

🎙 Interviewed Lawrence Lessig and Claudia Chwalisz in a deep dive on Democracy and Technology

Publications

* for first author contribution; (α) for alphabetical author ordering

AI-Enhanced Deliberative Democracy and the Future of the Collective Will

Manon Revel*, Théophile Pénigaud

Philosophy & Technology (2026)

Cultivating Pluralism In Algorithmic Monoculture: The Community Alignment Dataset

Lily Hong Zhang, Smitha Milli, Karen Jusko, Jonathan Smith, Brandon Amos, Wassim (Wes) Bouaziz, Manon Revel, Jack Kussman, Yasha Sheynin, Lisa Titus, Bhaktipriya Radharapu, Jane Yu, Vidya Sarma, Kris Rose, Maximilian Nickel

ICLR (2026)

Scaling Human Judgment in Community Notes with LLMs

Haiwen Li, Soham De, Manon Revel, Andreas Haupt, Brad Miller, Keith Coleman, Jay Baxter, Martin Saveski, Michiel A. Bakker

Journal of Online Trust & Safety (2025)

Arbiters of Ambivalence: Challenges of Using LLMs in No-Consensus Tasks

Bhaktipriya Radharapu, Manon Revel, Megan Ung, Sebastian Ruder, Adina Williams

ACL (2025)

Representative Ranking for Deliberation in the Public Sphere

Manon Revel*, Smitha Milli*, Tyler Lu, Jamelle Watson-Daniels, Max Nickel

Knight Symposium on Democratic Freedoms (2025) & ICML (2025)

Full-Stack Alignment: Co-Aligning AI and Institutions with Thick Models of Value

Joe Edelman, Tan Zhi-Xuan, Ryan Lowe, Oliver Klingefjord, Vincent Wang-Mascianica, Matija Franklin, Ryan Othniel Kearns, Ellie Hain, Atrisha Sarkar, Michiel Bakker, Fazl Barez, David Duvenaud, Jakob Foerster, Iason Gabriel, Joseph Gubbels, Bryce Goodman, Andreas Haupt, Jobst Heitzig, Julian Jara-Ettinger, Atoosa Kasirzadeh, James Ravi Kirkpatrick, Andrew Koh, W. Bradley Knox, Philipp Koralus, Joel Lehman, Sydney Levine, Samuele Marro, Manon Revel, Toby Shorin, Morgan Sutherland, Michael Henry Tessler, Ivan Vendrov, James Wilken-Smith

Position Paper (2025)

SEAL: Systematic Error Analysis for Value Alignment [Code]

Manon Revel*, Matteo Cargnelutti*, Tyna Eloundou, Greg Leppert

AAAI'25: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2025)

Tracking Truth with Liquid Democracy [Code]

(α) Adam Berinsky, Daniel Halpern, Joe Halpern, Ali Jadbabaie, Elchanan Mossel, Ariel Procaccia, Manon Revel*

Management Science (2025)

Toward Democracy Levels for AI

Aviv Ovadya, Luke Thorburn, Kyle Redman, Flynn Devine, Smitha Milli, Manon Revel, Andrew Konya, Atoosa Kasirzadeh

NeurIPS Pleuralistic Alignment Workshop (2024)

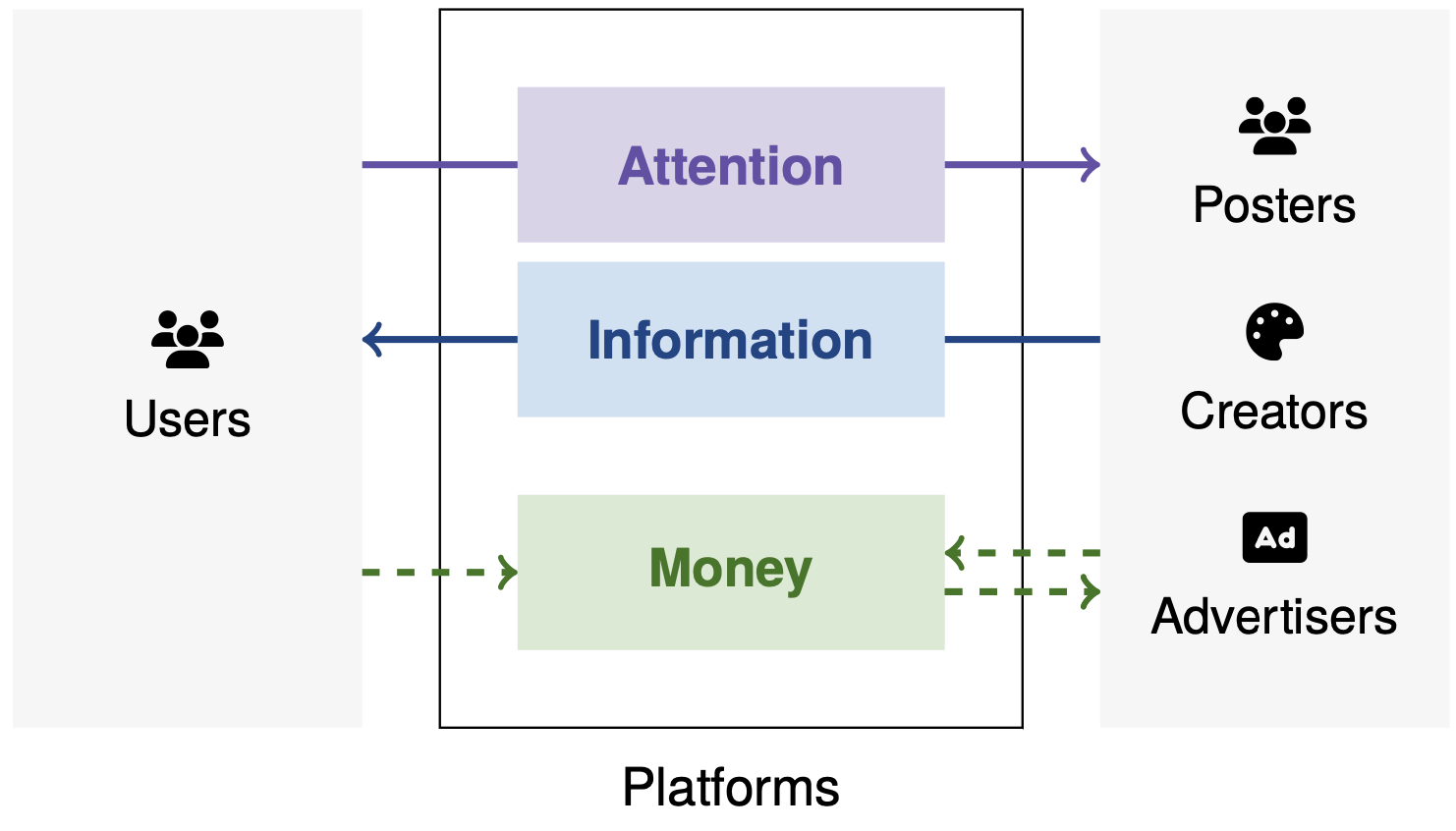

Mapping the Space of Social Media Regulation

(α) Nathaniel Lubin, Kalie Mayberry, Dylan Moses, Manon Revel*, Luke Thorburn*, Andrew West

MIT Science Policy Review (2024)

Enabling the Digital Democratic Revival: A Research Program for Digital Democracy

Davide Grossi, Ulrike Hahn, Michael Mäs, Andreas Nitsche, Jan Behrens, Niclas Boehmer, Markus Brill, Ulle Endriss, Umberto Grandi, Adrian Haret, Jobst Heitzig, Nicolien Janssens, Catholijn M. Jonker, Marijn A. Keijzer, Axel Kistner, Martin Lackner, Alexandra Lieben, Anna Mikhaylovskaya, Pradeep K. Murukannaiah, Carlo Proietti, Manon Revel, Élise Rouméas, Ehud Shapiro, Gogulapati Sreedurga, Björn Swierczek, Nimrod Talmon, Paolo Turrini, Zoi Terzopoulou, Frederik Van De Putte

Position Paper (2024)

Selecting Representative Bodies: An Axiomatic View

Manon Revel*, Niclas Boehmer, Rachael Colley, Markus Brill, Piotr Faliszewski, Edith Elkind

AAMAS '24: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems (2024)

How to Open Representative Democracy to the Future?

Manon Revel

European Journal of Risk Regulation 14 (4), 674-685 (2023)

In Defense of Liquid Democracy

(α) Daniel Halpern*, Joe Halpern, Ali Jadbabaie, Elchanan Mossel, Ariel Procaccia, Manon Revel*

EC'23: Proceedings of the 24th ACM Conference on Economics and Computation (2023)

Liquid Democracy in Practice: An Empirical Analysis of its Epistemic Performance

Manon Revel, Daniel Halpern, Adam Berinsky, Ali Jadbabaie

EAAMO'22: Equity and Access in Algorithms, Mechanisms, and Optimization (2022)

How Many Representatives Do We Need? The Optimal Size of a Congress Voting on Binary Issues

Manon Revel*, Tao Lin*, Daniel Halpern*

AAAI'22: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2022)

Vinaya Manchaiah, Alain Londero, Aniruddha K Deshpande, Manon Revel, Guillaume Palacios, Ryan L Boyd, Pierre Ratinaud

American Journal of Audiology 31 (3S), 993-1002 (2022)

Varieties of Resonance: the Subjective Interpretations and Utilizations of Media Output in France

Bo Yun Park, Adrien Abecassis, Manon Revel

Poetics (2021)

Native Advertising and the Credibility of Online Publishers

Manon Revel*, Amir Tohidi, Dean Eckles, Adam J Berinsky, Ali Jadbabaie (2021)

Research Projects

Teaching

University of Notre Dame

Deliberative Technologies for Democracy and Peace-building

Created a curriculum for the University of Notre Dame's Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies; covered political philosophy about democratic representation, mathematical theories of representation and algorithms for deliberation

MIT Media Lab

Decentralized Society, Cooperation and Plurality

Co-designed and taught Decentralized Society, Cooperation and Plurality seminar at MIT during IAP 2024

MIT Sloan

Data, Models, and Decisions

Co-assisted Professor Gamarnik in teaching an introductory class about probability, statistics and optimization for the MIT Sloan Fellows MBAs

MIT IDSS

Probability, Statistics, and Linear Algebra

Created and teach a 15-hour seminar in algebra, probability, statistics, and data science for the MIT Technology and Policy Masters Students

Media

Agency In An AI-Mediated World | UrbanAI

AI & Deliberation | Cooperative AI Foundation

Representative Ranking | Columbia University

Power and AI | Entretiens de Royaumont

Tech-enhanced Citizen Assemblies | MIT

Democracy & Technology | Harvard

CS Theory Seminar | Brown University

The Institutional Design Problem | MIT

Plurality Research | Berkeley University

Modeling Talk Series | Alphabet Google X

Liquid Democracy | ComSOC Seminar

Data and Models for Democracy | Datascientest

Futures of Democracy | Debating Europe

Mathematics & Democracy | CentraleSupelec

Virtual Conference on Computational Audiology

Information Wars | WiDS Conference

Miscellaneous

I love basketball, running, and windsurfing. Basketball gave me more than I could say — so in 2015, I founded the BeeGames, an association bringing together companies, universities, and pro athletes on the court under the patronage of NBA star Boris Diaw and former head coach of the French national team Pierre Dao.

I’m passionate about making science accessible and contribute to editorial content for the luminary French initiatives Les Entretiens de Royaumont and Les Rencontres Scientifiques.

Last, I enjoy hearing and telling stories in many forms. I’ve reported for the local radio Soleil de Ré, where I shared stories of local creative doers and hosted a daily chronicle during the 2012 Olympics. I produced the podcast Terre Américaine and founded The Fool on the Hill, the newspaper of Lycée Henri IV.